Men dominate media: in news rooms and stories, they get more exposure on camera, more by-lines and are quoted more often. An analysis of 2,353,652 news articles covering 12 topic categories from over 950 news outlets over a six month period ending in April, 2015 showed that mentions of men ranged from 69.5% in Entertainment to 91.5% in Sports. The only exception was Fashion, where women edged out men slightly at 54%. A more recent analysis by science writer Ed Yong of his STEM stories was similarly discouraging: only 24 percent of his quoted sources were women. Worse, 35 percent of his articles featured no female voices at all. Why does this matter? As journalist and editor Adrienne Lafrance noted in The Atlantic, the extreme gender imbalance in the media implies that the best voices are not those of women and misses out on diverse viewpoints, experiences and ideas. Journalist and field geophysicist Mika McKinnon is acutely aware of this gender differential in reporting and makes it a point to ask both men and women for expert comments. When making press requests, she is typically turned down more often by women. One case stood out: not one of 74 women requested for an interview obliged, contrasting with 11 of 15 men who agreed, including two who stated that they were not experts. She tweeted her frustration.

True story:

I made 74 press requests for women & 15 for men on [topic]. No women give interviews (although several suggested other names). 11 men gave interviews, 2 stating they weren’t experts.5:1 ratio. Still failed. https://t.co/3tK2WoDjV5

— Mika McKinnon (@mikamckinnon) January 4, 2018

https://platform.twitter.com/widgets.js

This tweet was seen over 792,000 times with more than 16,000 interactions, clearly demonstrating that the topic touched a nerve. We asked Mika to share her experience and her thoughts on the gender imbalance in journalism reporting.

Your Twitter thread about your experiences as a journalist in contacting women for interview really resonated with a lot of people. Why do you think that is?

We’re at a crossroads in North American culture where we recognize the injustices of our society and want something better.

I started my career in science, and participated in countless initiatives to recruit more women into STEM fields with me. In recent years, we’ve also started talking about the barriers that block women from progressing, or drive them out of science after they’ve devoted years of their lives to training and building experience. That basic injustice hurts.

When working as a science journalist, the conversation shifts to whose voices are given a platform. We express frustration at panels of all-men experts, then write stories that only feature those same voices. We’re having more and more conversations about how our habits creates an endless loop where coverage provides visibility and prestige, elevating those same voices disproportionately to others of similar professional caliber, and what we can do to break out and create new patterns.

It feels like every month, a new database pops up claiming to be the ultimate solution to finding new experts to showcase — BBC’s Expert Women, the Canadian nonprofit Informed Opinions, or more specialized databases like 500 Women Scientists. But like recruiting more girls to enlist in science majors doesn’t automatically mean we’ll have more women in senior professorships and agency leadership roles, journalists using databases of women in science addresses just one aspect of a big, monstrous problem that doesn’t solving the root injustices.

What I think resonated is taking something we know is a problem — underrepresentation of women in science, and particularly media coverage of women in science — and looked at how our superficial solutions of databases and goodwill aren’t enough. This isn’t a simple issue with a simple answer. It’s not about more women volunteering to talk to media, or about more journalists asking women for interviews, or even about the language we use when trying to overcome the barriers for why both those things don’t universally work. It’s looking at how even when you do everything right to make things better, sometimes that isn’t enough.

You noted a 5:1 ratio in how often men respond to requests for interview versus women. Why do you think this disparity exists?

The situation I wrote about on Twitter was an extreme abnormality for me. For every news article I write, I typically need two experts — one who worked on the research, and someone else from the same field of study who didn’t that can provide an outside opinion. This limits who I can talk to — not every study has a woman coauthor, and some fields have much greater gender disparities than others.

My ratios are usually about 75% of women initially turning down interview requests, dropping to 50% if I follow up to find out their reason for declining and work with them on a solution. Very few men turn down my interview requests, and when they do it is almost universally for logistics of being unable to schedule the interview prior to my deadline.

I had a particular story where I was getting grumpy over a 100% decline rate from women, particularly when I had only a 25% decline rate from the men I approached. I got stubborn about fixing it, ending up with a 5:1 approach rate (and still no women), so I tweeted about it because it was a particularly unusual and frustrating experience.

Of the reasons women experts give for not being able to give interviews, which do you think is the most important issue for the science community to be mindful of? How can we better address this in research training or professional development of women scientists?

The most common reasons women give me for declining interviews are:

- Lack of time – This is fair, as women receive disproportionate service demands, and something I don’t push back on.

- Discomfort with press – This is a self-perpetuating problem, but is something that can be addressed in part with media training by universities, professional organizations, or media agencies. It’s fair to ask for a someone more familiar with press to sit in on the interview (like an advisor or public information officer). Not every journalist can do this for every story, but it’s also fair to ask if it’s possible to get a list of questions in advance, or to review quotes prior to publication.

- Distrust of press – Pay attention to who is making the request. I teach experts to research bylines so they can evaluate the credibility of journalists. They can also check out the science coverage in the particular publication.

- Fear of repercussions – Women and other underrepresented people are often disproportionately punished for missteps, or become targets for harassment campaigns when they gain visibility. This is something I’ll talk to potential interviewees about, but it’s also something I won’t push on because it’s can be a real risk.

- Referral to greater authority – Even full professors will redirect me to more well-known names in the field (who due to increasing gender disparity with seniority, disproportionate award and prestige markers, and bias in media coverage, are usually men).

- Insufficient expertise – This is particularly true for graduate students, who despite actually doing the research, often decline by suggesting I talk to their advisors or team leaders (who due to the increasing gender disparity with seniority, are usually men).

- Unfamiliarity with exact topic – Women will typically turn down interview requests in their field if it does not directly overlap with their area of specialization, whereas men will frequently accept with a disclaimer like “I’m no expert, but…”

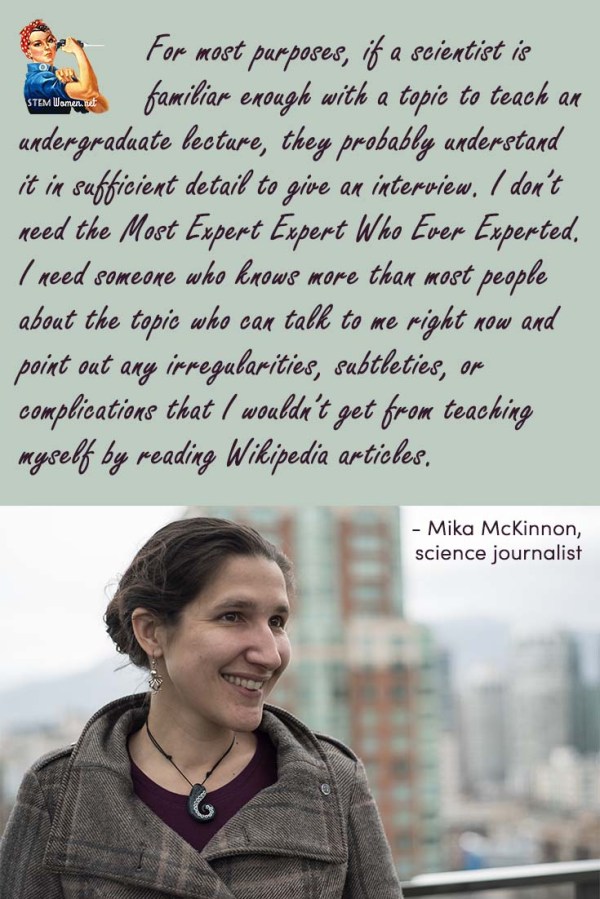

For all three of the last concerns, it’s important to understand that journalists are writing accessible articles, not technical articles. This means that interviews may be to teach the journalist background information, and it’s always to try to get quotes that can be used in the article. For most purposes, if a scientist is familiar enough with a topic to teach an undergraduate lecture, they probably understand it in sufficient detail to give an interview. I don’t need the Most Expert Expert Who Ever Experted. I need someone who knows more than most people about the topic who can talk to me right now and point out any irregularities, subtleties, or complications that I wouldn’t get from teaching myself about the topic by reading Wikipedia articles.

You gave excellent and practical advice for journalists to make women experts more comfortable about responding to media requests. Why do you think this is important?

No one person is going to solve the problems of gender bias in science or in media. We’re all in this together, and we all need to use our expertise and skills to help each other out to make things better than they are right now.

What else do you think journalists can do more of, to ensure fairer representation in the media?

The most important thing for journalists to do is pay attention to whose voices they are showcasing and why. After that, following up to understand why they’re not getting the diversity of voices they want to cover is important, and be flexible on addressing the barriers preventing people from participating.

How did your journalist peers respond when you shared this story?

Many shared their own stories, resources for finding women experts, reasons they get turned down, and tips they have for solving barriers. I also heard from event organizers who shared similar problems.

But from some, I also heard disbelief or shock. These reactions were typically from people who don’t pay attention to the people they approach as sources, who will hopefully start paying attention in the future!

Mika, you are a field geophysicist, disaster researcher, scifi science consultant and science writer. What advice would you give women scientists considering following a similar path in consulting and science writing?

My job is to be excited and curious in public. I currently find it rewarding to do a diversity of jobs that allow me to do this in different ways, but it’s not a path for everyone. If you want to freelance, the most important things are to be creative in how you apply your skills, organized in your assignments, and reliable in being competent at work.

About

Mika McKinnon is a consultant, public speaker and writer based in Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada. She has trained as a geophysicist specializing in disasters, including tsunami, earthquakes, asteroid impacts. Ask her to bring science to your fiction, write a story, run a workshop, give a talk, or more! Follow her on Twitter @mikamckinnon

Read Mika’s advice to journalists seeking women experts below!

Challenges Overcoming Bias in Science Coverage https://platform.twitter.com/widgets.js